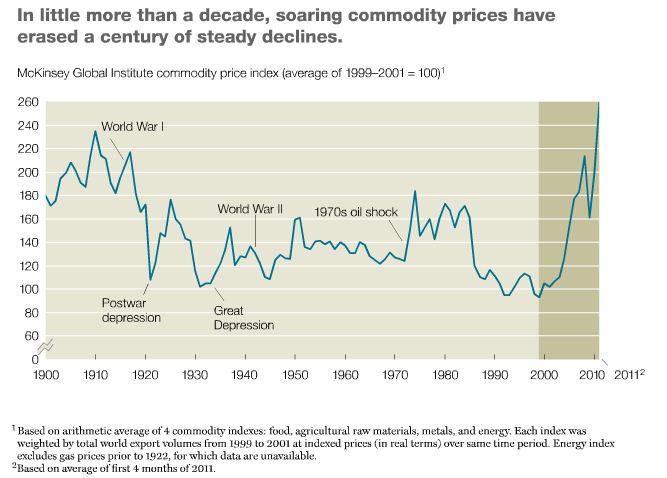

“Cheap resources underpinned economic growth for much of the 20th century. The 21st will be different”

McKinsey Quarterly är konsultbolagets egna publikation. Den har en inriktning på att lyfta fram nya trender och omvärldsförändringar som påverkar hur företagen bör agera.

I deras artikel “A new era for commodities” går man ut hårt med följande diagram.

Sedan följer en beskrivning av hur efterfrågan på råvaror kommer att fortsätta öka (inte minst pga Kina och Indien) och att det nu är betydligt svårare att öka utbudet på det sätt som man gjorde under 1900-talet. Detta pga 1. klimathotet 2. utvinningen är komplexare och dyrare 3. när resurser nyttjas fullt ut / till bristningsgränsen finns det risk för negativa spridningseffekter:

“Demand for energy, food, metals, and water should rise inexorably as three billion new middle-class consumers emerge in the next two decades.1 The global car fleet, for example, is expected almost to double, to 1.7 billion, by 2030. In India, we expect calorie intake per person to rise by 20 percent during that period, while per capita meat consumption in China could increase by 60 percent, to 80 kilograms (176 pounds) a year. Demand for urban infrastructure also will soar. China, for example, could annually add flor space totaling 2.5 times the entire residential and commercial square footage of the city of Chicago, while India could add floor space equal to another Chicago every year.

Such dramatic growth in demand for commodities actually isn’t unusual. Similar factors were at play throughout the 20th century as the planet’s population tripled and demand for various resources jumped anywhere from 600 to 2,000 percent. Had supply remained constant, commodity prices would have soared. Yet dramatic improvements in exploration, extraction, and cultivation techniques kept supply ahead of ever-increasing global needs, cutting the real price of an equally weighted index of key commodities by almost half. This ability to access progressively cheaper resources underpinned a 20-fold expansion of the world economy.

There are three differences today. First, we are now aware of the potential climatic impact of carbon emissions associated with surging resource use. Without major changes, global carbon emissions will remain significantly above the level required to keep increases in the global temperature below 2 degrees Celsius—the threshold identified as potentially catastrophic.2

Second, it’s becoming increasingly difficult to expand the supply of commodities, especially in the short run. While there may not be absolute resource shortages—the perceived risk of one has historically spurred efficiency-enhancing innovations—we are at a point where supply is increasingly inelastic. Long-term marginal costs are increasing for many resources as depletion rates accelerate and new investments are made in more complex, less productive locations.

Third, the linkages among resources are becoming increasingly important. Consider, for example, the potential ripple effects of water shortfalls at a time when roughly 70 percent of all water is consumed by agriculture and 12 percent by energy production. In Uganda, water shortages have led to escalating energy prices, which led to the use of more wood fuels, which led to deforestation and soil degradation that threatened the food supply.”

Sammanfattningsvis är det alltså en ganska utmanande situation vi befinner oss i.

Lyckligtvis finns det lösningar som låter oss köra på! Det är temat för uppföljningsartikeln Mobilizing for a resource revolution. Artikeln börjar med historiska exempel då man trott att resurserna inte skulle räcka längre, men då man räddats av marknadskrafter och innovationer. Gissa om det är möjligt även denna gång? Dock konstaterar man att “Nothing less than a resource revolution is needed”.

Klart att man blir lite nyfiken på att läsa mer om hur problemlösarna på McKinsey Global Institute, Sustainability & Resource Productivity Practice angriper den här svårlösta ekvationen. Jag varnar för antiklimax. Trots att McKinsey menar att det krävs en revolution för att hantera utmaningen så dribblar de förbi huvudproblemet med att konstatera “Our analysis suggests that it’s possible to meet the resource challenge through an expansion in supply and base-case productivity-improvement rates. “

Aha! Den ökade efterfrågan kan mötas med ökat utbud! Och produktivitetsförbättringar!

Dessutom finns det två vägar att välja på. Den ena är ökat utbud och produktivitetsförbättringar i enlighet med nuvarande takt,vilket kräver ca 3000 miljarder USD i investeringar per år (1000 mer än idag). Den andra är en mindre ökning av utbudet som kompenseras av större produktivitetsökning till den något högre kostnaden av 3200 miljarder USD.

Resten av artikeln innehåller vettiga tankar om hur verksamheter påverkas och kan agera i den nya eran med högre och mer volatila råvarupriser.

Slutklämmen lyfter också ett varnande finger om att det inte är en riskfri framtid vi igår till mötes. Det kan leda till negativa effekter på tillväxt, välfärd och politisk stabilitet (hoppsan!). Men även om det skulle bli besvärligt på vägen så är man noga med att poängtera att tekniken kommer lösa problemen förr eller senare!

“Supply and productivity opportunities can address the growing demand for resources and the environmental challenges associated with the rise of three billion new middle-class consumers. But these opportunities raise fresh questions: can business and government leaders, not to mention consumers, move with the speed and scale needed to avoid a period of dramatically higher resource prices, along with their destabilizing impact on economic growth, welfare, and political stability? Or do we need a crisis, with its associated problems, to accelerate technological innovation and investment? The questions are big, and the stakes are high.”

McKinsey räknar i sina efterfrågeökningsprognoser med ca 3 miljarder nya medelklasskonsumenter och dubbelt så många bilar inom kommande 20 år. Jag skulle gärna vilja se vilka antagande de har gjort om tillgången på olja för den perioden..